Valor Histórico de las Pizarras de Bernardos > The works with Bernardos slate in the 16th and 17th centuries

It is a difficult task to list all the works which used slate extracted in Bernardos, not due to a lack of documentation, but because there is a risk of not being exhaustive. It is even more complicated to indicate the type of carried out − whether it was a new construction or repair work − since the introduction of slate as roofing material did not lack of problems. Although slate could boast a long lifespan, it was still vulnerable to the passage of time and to accidents such as fires and storms which often could destroy roofs, the most exposed part of the building. It is noteworthy that buildings such as the Monastery of El Escorial had to be repaired several times because of fires, such as the terrible fire of 1671 or in 1732, not to mention all the buildings which were left in ruins or disappeared. In some instances, the demand for slate manifests itself in the state of ruin of the building’s spires, as was the case in 1716 with the Palace of Cardinal Espinosa in Martín Muñoz de las Posadas.

In any case, it is necessary to meticulously read through the documents, as slate was usually used as decorative element to cover towers or spires. Its high cost meant that it was difficult to completely cover a building with slate only. It is true that the buildings sometimes underwent transformations which led to a replacement of the spires’ covering material: either originally covered in slate before the latter was substituted for brick tiles − as was the case with the palace of the Duke of Lerma, or the opposite scenario, as was done in the Casa del Pardo in the 1560s. Therefore, a careful study of the various constructions undertaken must take into account these elements in order to clarify whether it was a case of maintenance, repair, new roofing or reconstruction following an incident.

In this sense, it is must be borne in mind that other specialised sectors contributed to this new construction style, for example, the carpenters who built the wooden frames, and the slate masters who placed the slate as well as other complementary materials such as lead. It has previously been mentioned that, in 1562, eight slate masters had been contracted, brought in from Flanders, mainly from Brussels and Liege. Later documentation indicates the presence of French slate masters and the first Spanish ones, such as Gonzalo López and Pedro Muñoz. From the early 1570s, the name of Antón de Barruelos appears, as he took care of the roof for the Palace of El Escorial, and later on, during the first decades of the 17th century, many more Spanish slate masters are mentioned, such as Juan García de Barruelos, who contributed to important buildings such as the Imperial College of the Society of Jesus or the Palace of the Duke of Uceda in Madrid, or Pedro de Segovia or Pedro Martín de Monesterio.

However, the appendix contains a reference to the works undertaken with slate from Bernardos between the 16th and 19th century. In the coming pages, we will detail some of the most important constructions and establish the context surrounding them.CONSTRUCTIONS WITH SLATE DURING THE 16TH CENTURY

As previously mentioned, the opening of the Bernardos quarries coincided with the renovation of a great portion of the royal buildings situated in the vicinity of Madrid, which Philip II eventually converted into the Kingdom’s capital city in 1561. For this reason, the list of buildings with slate roofs is very much linked to this renovating process. There are three constructions which simultaneously received the first deliveries of slate: the palace of Valsaín in the forest of Segovia, the palace of El Pardo and the Royal Alcázar of Madrid and its annexes (royal stables and armoury). It is thought that the first completed autonomous piece made with slate was the so-called Golden Tower, on the south-west corner of the Royal Alcázar of Madrid. However, although it seems that the intention was to renovate all the roofs, this was not always done with slate. Lead was used in Aranjuez and brick tiles in Aceca. Similarly, it appears that the roof of the Alcázar of Segovia was also made of lead, particularly in the first phase of its renovation.

In the construction of the Palace of Valsaín − the so-called “Forest House” − which was led by Gaspar de Vega, the roofs and towers started being built at the beginning of the 1560s. In this respect, the paintings of Anton van de Wyngaerde from his stay at the Palace in 1562 are very illustrative. Anton van de Wyngaerde was a draftsman and natural landscape painter from Antwerp who was commissioned by Philip II to tour Spain and paint landscapes of various cities. The painting depicting Valsaín captures, thanks to the magnificent detail of the drawing and the choices of colour, the substitution of the existing roof with a slate covering. Another witness of the works in 1562 is the canon Juan Rodríguez, quoted by Llaguno, who spoke of the placement of slate on the towers of the Palace of Valsaín and mentioned the possibility of using it for the Cathedral of Segovia.

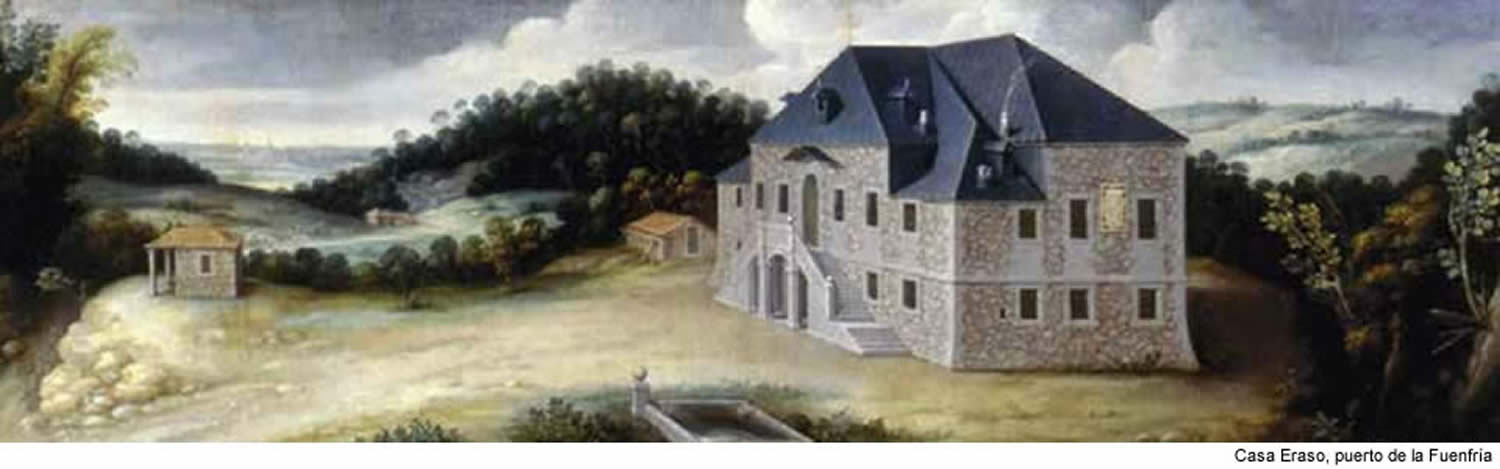

Slate was simultaneously sent to Madrid for the works which were underway in the stables located in the vicinity of the Royal Alcázar and in the roof of the Golden Tower. The Palace of El Pardo, a country house located close to Madrid and used since the Middle Ages because the nearby forest of the same name was a royal hunting ground, is another of those early constructions which received slate for the roof. taking into account that in this case, the previous roof was completely dismantled to make way for the new material. Another edification which probably started in the early 1560s was the Eraso House − nowadays left in ruins − located in the mountain pass of Fuenfría, in the mountains of Guadarrama between Segovia and Madrid. Although there is no record of direct witnesses of the slate works in this case, we do know that the slate master Pedro Muñoz repaired the roofs of the house in 1607.

It is difficult to measure the quantity of slate that was required for these works, but there is data which allows us to gauge the weight of the material sent to the constructions and thus to make estimations about the pace of exploitation. For example, for the construction of the Royal stables, more than eleven thousand arrobas were brought in between 1563 and 1566. Translating this weight into kilograms and taking into account the above-mentioned information on the weight of the slate pieces − around one kg each, it would mean 126.5 tons, that is, 126.000 pieces of slate.

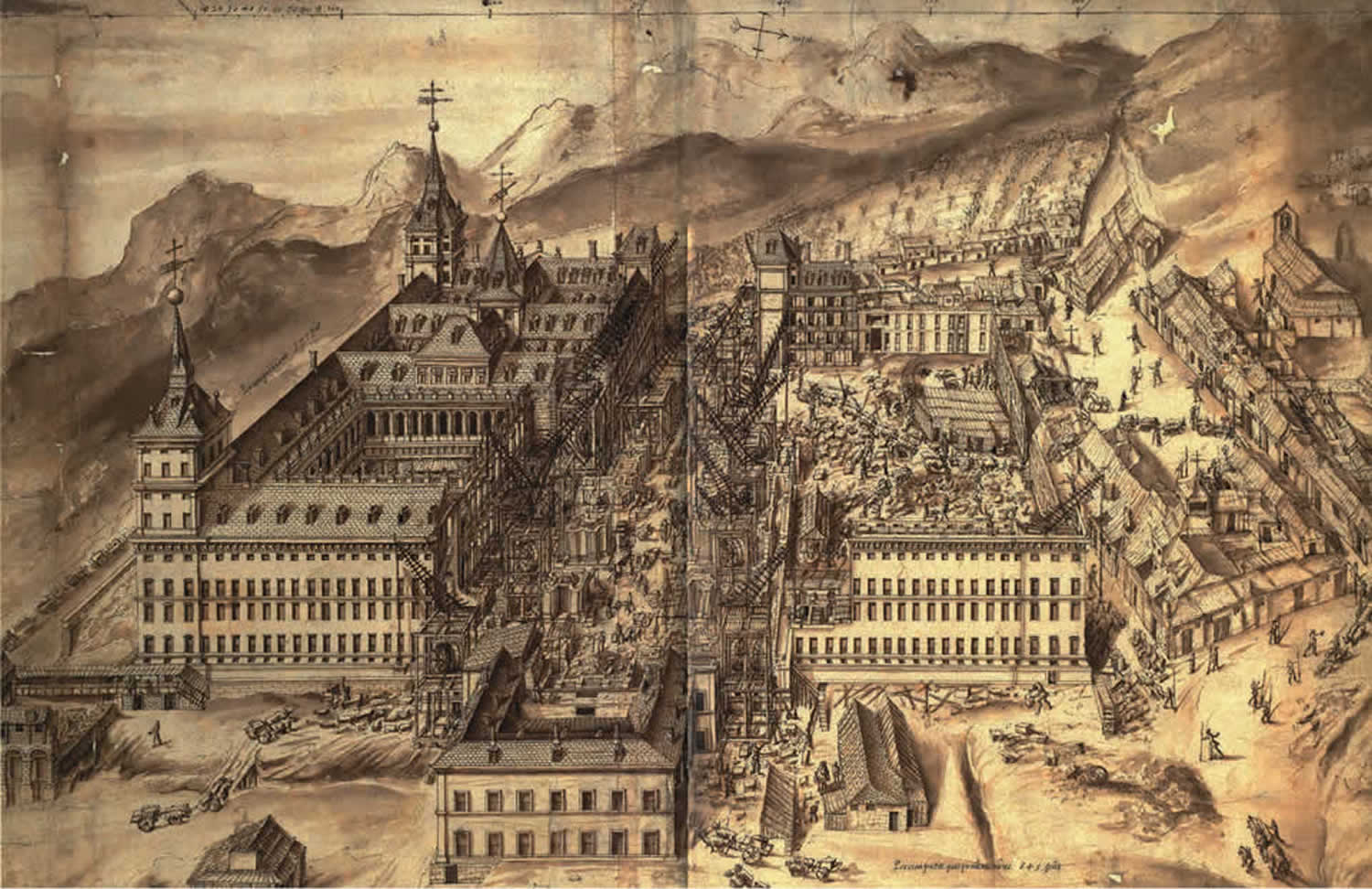

The construction of this period par excellence − in which slate stands out as a distinctive element and which represents the bulk of the quarry exploitation for many years − is undoubtedly Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial. Two earlier constructions in the same area had also used slate: La Herrería and La Fresneda, two country houses with slate roofs. The Monastery of San Lorenzo was, however, the most impressive building, standing out as the model of the new style and representing a full identification with the monarch who promoted this style. The words of Jonathan Brown − one of the world’s most renowned authorities in art history − summarise the significance of El Escorial in the definition of a personal style preference imposed by the King:

“The unadorned style of El Escorial was the creation of King Philip himself, expressed through the work of his architects. The style was based partly on a rejection of existing Castilian models and a drive towards Italian models. However, the Italian Renaissance style was drastically adapted in Spain to eliminate anything that could be perceived as ornamental, superfluous or sensual. The only elements that were preserved were those related to scale, mass and proportionality, which were freely manipulated to produce an effect of austere grandeur as envisioned by the King. The unusual and odd combination of these characteristics with the Flemish-style slate roofs is an unmistakable reflection of the Philip’s personal taste”.

The undeniable author of the Escorial style in terms of the roofs and towers is Juan de Herrera, an architect who took over the management of the works in El Escorial following the death of Juan Bautista de Toledo. Juan de Herrera contributed with his own personal vision − different from the ones underlying earlier constructions − in the style of the towers which served as a model for later architectural works carried out by Francisco de Mora and Juan Gómez de Mora in the first half of the 17th century.

The amount of slate extracted for this construction considerably exceeds the quantities used for previous works. For this reason the quarries of Bernardos met the demand followed the orders of the authorities administrating the construction of the monastery by designating overseers and adapting the daily management of the quarries, as can be seen in the various instructions sent out in the 1570s and 1590s to regulate the functioning of the quarry and the shipment of slate to the construction site. This link between El Escorial and the Bernardos quarries continues undisrupted since the 16th century into the present day thanks to the successive alterations and roof maintenance works.

The expansion of the Habsburg style with the slate roofs and towers was not limited to royal works. When it came to erecting palaces, many people in the royal milieu opted to copy the new fashion and the slate from Bernardos was thus also transported to other places. The King granted his authorisation for the material to be used in palaces commissioned by his close collaborators. In 1570, the Cardinal Diego de Espinosa − president of the Council of Castile − requested slate for the roof of the palace which he was building in Martín Muñoz de las Posadas and was granted the royal permit not only for the slate but also for the related ironwork. The slate delivery took place throughout 1571 and in the early months of 1572, additional pieces of slate were received to build the base of the courtyard’s fountain.

Another construction to use slate was the palace/house of Diego Vargas, the King’s secretary, situated in Torre de Esteban Hambrán in the Toledo region. The construction started in 1569 but the roof works were still ongoing in 1576. In 1574, Diego de Vargas asked the King for fifty loads of slate, which were granted through a royal order on 28th June. Since 1575, slate was extracted from Bernardos for this construction. Three loads were sent out by the end of the year and, at the beginning of 1576, the overseer Juan Sánchez de Talavera received additional instructions on this order, reminding him of the payments to be made for the workers’ wages and the use of the tools, and of the characteristics of the material to be extracted.

Another construction which stands out due to its commercial significance is the Casa de la Moneda in Segovia, one of the centres for the mintage of the Spanish Crown’s coins. It was equipped with innovative technology from central Europe, notably machinery powered by hydraulic energy. The Casa de la Moneda was built on the basis of a project drawn by Juan de Herrera in the 1580s and in which Pedro Muñoz was the slate master.

CONSTRUCTIONS WITH SLATE DURING THE 17TH CENTURY.

During the reign of Philip III at the beginning of the 17th century, almost no important constructions were initiated by the monarchy. Due to the crisis situation and his father’s building frenzy, the existing palaces exceeded the court’s needs. Philip II had undermined the prospect of any new construction, given the difficult circumstances the Crown was facing. However the style and the fashion did not disappear, but spread in the various constructions undertaken in the court’s entourage. The most important figure during this reign is Diego de Sandoval, Duke of Lerma, who became the King’s favourite and erected a palace and monastery complex in the city of Lerma, in the Burgos region. This palace was the main construction to follow the steps influential figures from the previous reign such as the palace built by Cardinal Espinosa. According to the available information, the roof of the Lerma palace was made of brick and only the tower tops were covered in slate. The slate master for these works was Pedro Muñoz, then administrator of the Bernardos quarries.

Nevertheless, slate was still extracted for the maintenance of previously-built royal buildings, and some important works were undertaken such as the towers of the Monastery of Uclés in the province of Cuenca, an impressive construction initiated during the previous reign. Slate towers became more widespread in the decoration of churches, and in noble residences such as the palace of the Duke of Uceda in Madrid, which featured the participation of Juan García de Barruelos, and slowly established themselves as a representative motif of the period in various locations.

Philip IV then became King and chose the Count-Duke of Olivares as his favourite, and the most representative edification of this reign was the Palace of El Buen Retiro. This palace was designed as a majestic space of recreation for the Court, with a large tree-covered park, ponds, etc., and built to become the stage of the grandeur of the monarchy, although the situation of war in Europe and the constant need for funding for the war efforts meant that the construction relied mainly on cheap materials, with walls and facades made of brick and roofs made of mud tiles. Slate was only used for the towers and spires, as well as for the roofs of certain chapels inside the grounds and for the main arch for the water supply of the complex.

A contemporary construction of the former is the Zarzuela Palace, also located outside of Madrid and also used as recreational estate in the vicinity of the forest of El Pardo, currently the residence of the Spanish royal family. Similarly, slate was introduced in civilian constructions outside of the royal milieu, such as the town halls of Madrid and Segovia, and decades later the Valladolid town hall, the Casa de la Panadería in the Plaza Mayor of Madrid or the Court’s Royal Prison, currently the seat of the Spanish Foreign Ministry. Juan Gómez de Mora, the nephew of Francisco de Mora, took on the role of master builder for the royal works and of architect for the Madrid town hall, and became an indispensable figure in the expansion of slate-covered buildings in the Spanish capital city during this period. This also extended to religious buildings, such as the Monastery of Dominican nuns in Loeches, sponsored by the Count-Duke of Olivares, Philip IV’s right hand, or the Collegiate Church of San Justo y Pastor in Alcalá de Henares.

During the reign of Charles II, the most important slate works were the repairs of the damage caused by a voracious fire on the monastery of El Escorial in 1671. On the 7th of June, a chimney caught on fire in one of the monastery’s wings, and the wind fuelled the flames which spread over a great part of the roof, damaging the underlying wooden structure and the covering slate. The spires of four towers were ruined, as well as all roofs except those of the church, the royal quarters and the main library.

This fire destroyed the majority of the slate roofs, which had to be repaired again. The works started in July 1671 and by the 23rd February 1673, 152,204 slate pieces had been sent, weighing 15,776 arrobas, that is, approximately 181,424 kg. The cost is estimated to have been 42,283 reales.

In any case, the slate constructions continued becoming more widespread in major buildings during this period, as illustrated by the orders of slate to cover the spires of the Plaza Mayor in Salamanca, or those of the churches of San Millán and San Esteban in Segovia, or to tile the Cathedral of Segovia.

THE 18TH CENTURY. THE TIME OF THE BOURBONS

At the beginning of the 18th century, the arrival of the Bourbon Dynasty to the Spanish throne in the person of Philip V, the grandson of Louis XIV of France, gives birth to a change in architectural style in which French models, and more concretely the Palace of Versailles, become the reference point.

In this context, the most significant construction is the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso, built during the 1720s. The newly built palace was located in the vicinity of the forest of Valsaín, very close to the location of the former palace, which had been left in an regrettable state after a great fire in 1695. The Palace of La Granja was used as a summer residence for the court, designed to include a garden space with numerous fountains and surrounded with a series of other installations and buildings, amongst which the Royal Factory of Glass and Crystal is the most notable. The roofs of the Palace of La Granja and its annexed buildings were also covered with hundreds of thousands of pieces of slate from Bernardos. Another significant construction during the 18th century is the foundation of the Convent of the Salesas Reales in Madrid, which was commissioned mid-century by Barbara de Braganza, wife of Ferdinand VI, the son of Ferdinand V. The Convent was located in the spot in which now lies the Spanish Supreme Court. These constructions newly impulsed the exploitation of the quarry, with a significant increase in the number of workers and mass production in Bernardos as much as in Carbonero el Mayor. However, this epoch also witnessed the disappearance of certain distinctive elements from the architectural period of Philip II, such as the aforementioned Palace of Valsaín, which did not recover from the fire of 1695, and the Royal Alcázar of Madrid, the victim of another tremendous fire which occurred during Christmas time in 1734 and left most of the building in ruins. This led to the construction, on the same grounds, of the current Royal Palace, designed by Giovanni Batista Sacchetti.

Nevertheless, it must be observed that slate became more widespread, and increasingly stated to be used in religious buildings, usually to highlight the upper parts, spires and towers, as can be seen in numerous churches in the provinces of Toledo, Madrid and Segovia; convents such as the Carthusian Monastery of Santa María de El Paular or hermitages such as the Hermitage of the Virgen del Puerto in Madrid, designed by Pedro de Ribero (see annexes). Albeit in modest quantities, some slate was sent to works situated further away in Navarra (Viana) or in the Basque Country (Asteguieta).

(26) AGP, San Ildefonso, Cª 13541, 1716. En la carta se dice que se hospedó Carlos II con la reina en 1690.

(27) El palacio del duque de Lerma en la población burgalesa homónima se cubrió de teja (L. Cervera, pp. 471 y 484.

(28) Referencias más amplias sobre los pizarreros cubridores, en Ceballos, 2010, p. 78-81.

(29) Llaguno, II, 48.

(30) AGP. Cª 9380, exp. 7.

(31) Llaguno, II, 229.

(32) L. Cervera Vera, 1977.

(33) Marías, 1986: 223-4.

(34) Llaguno II, 230.

(35) Ver el desarrollo de este proyecto en L. Cervera Vera 1967.

(36) No había sido el único incendio en El Escorial, ya que se registran otros, como en 1642 AGP, San Lorenzo, Patrimonio, leg 1826) o en 1732, pero sin duda es el más importante.

(37) Santos, Descripción (1698: 6).