Company > History >Historical value of the Bernardos slates > Organisation and exploitation of the quarries. Personnel employed and tools

The exploitation of the quarries required specialised personnel who understood how to carry out the tasks of prospecting and extracting the material, but also nonspecialised workers to assist with the strenuous work of levelling, clearing debris and transporting the rocks. In addition, part of the cutting work and elaboration of the pieces also took place in the quarries before the pieces were transported to the construction sites. Therefore, miners and slate extractors made their way to Bernardos to take over the exploitation of the quarry, along with other workers in charge of cutting and fabricating the pieces for the roofs. There were thus two main specialised functions: on the one hand, extracting, and on the other hand, working on the material and transforming it into the pieces then used on the roofs. The increase in the activity in the Bernardos quarries, the specialisation of functions and the necessity for a minimum organisation to take over the daily management raised the question of the need to find a supervisor for the everyday work. An overseer of the quarries was thus designated – later renamed “administrator” – who was in charge of transmitting orders related to the requests for the material, preparing the weekly payslips for the personnel, planning the tasks ahead according to the directives of the higher entities and maintaining the tools. Some overseers lent tools to individual workers, such as Sebastián Pérez, who declared in his will that he lent such instruments as mattocks and bars – something which subsequent instructions sharply prohibited doing. The workers organised themselves in groups to work together in given spots, since several groups could work on different spots depending on the intensity of the work in that area.

The first specialists to arrive were miners from Burgundy who took care of extracting the first shipments that were then sent to Valsaín and Madrid. The earliest payslips found were from 1561 and relate to the presence of two miners, Jean de Bordeaux and Antoine de Hosbo, both from Fumay, a French town in the Ardennes region, and of two workers from Santa María de Nieva who assisted the Burgundian men. There was also a local man from Bernardos who took the slate to the works site in Valsaín. Subsequently, at the end of 1562, Gaspar de Vega sent Jean Ru and Gonzalo López, a French and Spanish slate master, respectively, to find and bring back more specialists from France. The latter arrived in 1563 – some of them with their families – from the French region of Angers, more precisely from Saint Leonard, one of the main slateproducing areas. Gaspar de Vega announced their arrival in midMarch affirming that

“they are very good apprentices, both are married and bringing their wives, and they are both young”

and that their wages would be lower than the workers previously hired for this job. More men arrived later, so that in total there were eight foreign specialists.

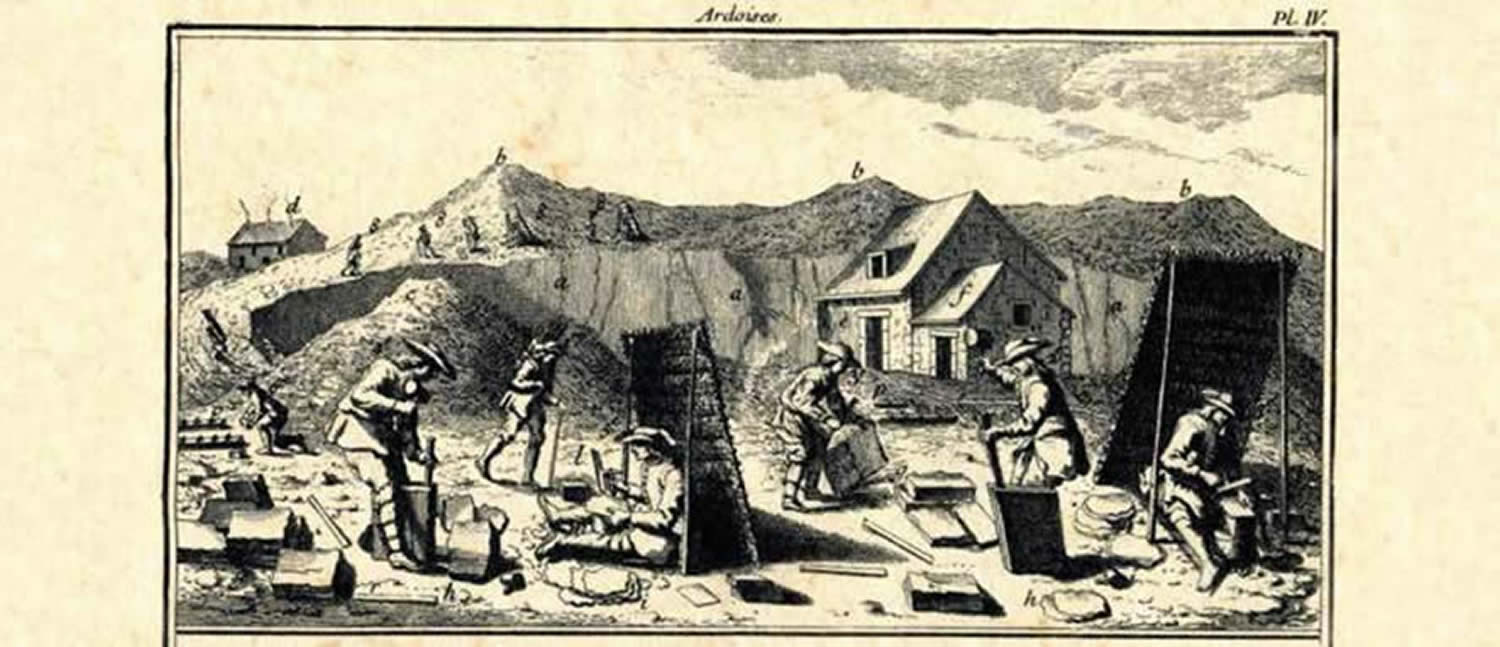

Groups were formed to organise the exploitation. When times were not too busy, all men worked in the same location carrying out different tasks: first, one had to clear and dig up the river bank with mattocks and pickaxes – this was done by labourers. The “extractors” hauled out pieces of rock in the shape of thick blocks. The “beaters” used mallets and wedges to split the blocks and make them manageable. The “cleavers” slit the pieces open and the “cutters” exfoliated the rock until it reached the dimensions required for the slate. Labourers were given secondary tasks. In times of high demand, the work had to be carried out in various deposit locations and the habitual tasks were distributed among the active work groups.

The working hours usually followed the sun. There were two different periods: during the period between the day of Santa Cruz in May (May 3rd) and the day of Santa Cruz in September (September 14th), the workers had shifts from 6am until sunset; during the rest of the year, they started one hour later and worked until sunset. Since the working day was much longer in the summertime, a break of two hours was granted for lunchtime, and another hour for an afternoon refreshment. By contrast, the only break during the wintertime was one hour for lunch.

The daily wages handed to the workers varied depending on their specialisation. The foreign experts received the highest salaries and the amounts decreased from there, with the labourers at the bottom of the scale. Not all foreign experts received the same wages, however, as the Burgundian experts had higher salaries than the French ones.

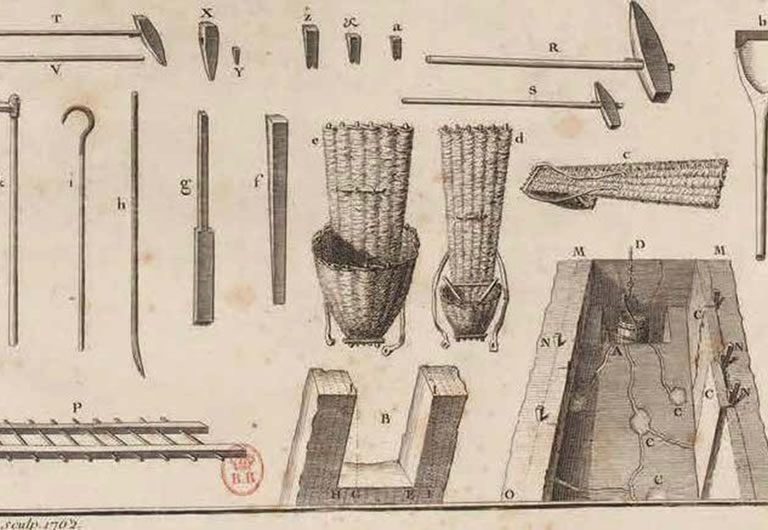

In order to carry out the tasks required, the quarry workers could count on a good collection of tools, many of which were similar to those in the illustration below showing the tools used in French quarries in the 18th century: mattocks, shovels and pickaxes to clear and uncover the banks, mallets or maces to strike the variouslysized wedges which were used to open up the banks, bars with hooks or with a flat and narrow end to move and lever up the banks, mallets made of holm oak wood to strike the shimming and exfoliating tools, and cutting tools to shape the piece into the required dimensions. Hand barrows were necessary to haul the debris and carry the pieces from the quarries to the crafting location. A chopping block was used to rest the slate in order to split it open.

Due to the large quantity of tools used and to the need to maintain them, it became necessary to have a forge inside the quarry. Like all other forges of that period, the quarry forge used charcoal and bellows to keep the flame alive and the temperature high, as well as grindstones. In the forge, the tools were readied, the mattocks, pickaxes and wedges sharpened. New tools were also fabricated, such as choppers and wedges, which needed to be put through a process whereby steel was poured on them to make them harder and thus more effective for work. In the 1570s, Francisco López − son of the blacksmith who ran the village forge − worked in the quarry forge. According to the 1575 decrees, he received two reales and one cuartillo for each of work and the charcoal which he used, but his wages were adjusted if there was more work. By 1581, his salary had reached three reales and 14 maravedis, and was further increased to four reales a few months later, but this meant that Francisco had to abide by the schedule of the other tasks and, if work demanded it, stay until he finished sharpening the tools needed for the next day. In addition, if there was no forging work to be done, he had to join the extracting work. However, when the workload was heavy, he was assigned a labourer to assist him. The quarry also included a house to store the slate.

In times of high demand for slate, workers from surrounding villages joined the workers from Bernardos, often arriving to the quarry by foot. During the exploitation of the Arco quarry, workers from Armuña, Carbonero and Mozoncillo were employed, while at the Castillo quarry, the labourers were from Miguelibáñez or even Melque. In the 16th century, in the periods of strongest activity, it is thought that around fifty workers were employed in the quarries, but there were attempts to avoid hiring too youbg or old people young or too old, hiring relatives as a favour or even simply hiring too many employees, as shown in the orders received by the administrator in 1587:

“… keep the number of total workers − counting experts, daily workers and labourers − down to approximately 30 at all times, lest you should want to pay their wages from your own pocket, and maintain these numbers until you are told differently …”

The French technicians who arrived in the 1560s worked in the quarries during the reign of Philip II, but were gone by the turn of the century. Some returned home, and others died in Bernardos while their families returned to Angers, as was the case of Juana Bancor, wife of Arné Godre, who arrived in 1574. Lastly, some took root in the village and married local women, such as Juan Morreo who married Ana del Castillo, the sister of master extractor Juan del Castillo, or Fabian Lambasi, who took Ana Sanz as his wife.

The overseers of the royal constructions were concerned with the learning of the profession of extracting and crafting the slate. For this reason, they sent out clear instructions stressing the need to have apprentices who were capable of assimilating the knowledge. Juan del Castillo was one of the first Spaniards to reach the rank of technician. Records from 1581 read:

“… Juan del Castillo shall go slitting and cutting the rocks with an apprentice who must be taught this profession. This apprentice will be Alonso García, son of Pedro García, a neighbour from Bernardos, as was recommended to us and agreed upon with him. And Juan del Castillo must receive one real each day this year of 1581, so that he keeps an eye on Alonso while he learns to shim and so that he teaches him this profession. The next year in 1582, Juan del Castillo must receive one real and a half each day and henceforward he must be paid based on his work, that is, for the days in which he indeed works, and should said Alonso Garcia be found not as able and well-performing as is required, he can be dismissed and replaced by another apprentice whom the overseer deems worthy … ”

Juan del Castillo later taught the trade to his son Antonio. The latter used this advantage when he proclaimed the merits of his experience in order to be granted the rank of administrator, a role which was passed on within the family for generations. In the document which appointed Antonio del Castillo as administrator in 1629, he was ordered to:

“… serve and work in the quarries when it becomes necessary to extract slate for the construction of my houses and other royal buildings (…) and you are not allowed to give or sell slate to anyone without a licence or an order from me. In like manner, you are obliged to teach this profession to your two sons and to any other person whom I shall designate, so that my kingdom should never lack people who know and can practice this trade (…) ”

In the document which announced the appointment of Juan del Castillo as administrator in 1663, it was recalled that he had:

“been educated in the work of the quarries, as you helped your father for more than twenty years in extracting slate …”

The overseers or administrators who managed the quarries − and without whose authorisation it was impossible to extract slate for constructions − were the King’s officials, and, as such, were granted certain privileges, such as certain positions as councilmen or exemption from military duty. They earned 15.000 maravedis annually, but this sum was reduced to half from the middle of the 17th century onwards, as they had to pay a tax which took half of their wages.

In 1738, a conflict for the position of administrator arose between Juan del Castillo and Silvestre de Segovia. They were close relatives. At first Juan del Castillo received the appointment at the beginning of 1738 at the request of the manager of San Ildefonso. The document detailing this appointment does not proclaim Juan’s merits in terms of working at the quarry, but affirms that “he knows the quarries, can read, write and count well, and is reasonable so as to be able to work with the extractors.” However, Silvestre de Segovia voices an appeal against this appointment and flaunts his experience as extractor for twenty three years, as well as that of his father and grandfather for more than seventy; and adds that his father had opened a plentiful quarry, bearing the cost himself. Silvestre de Segovia was eventually given the position. This did not prove fruitful for him in terms of pay, however, as he presented a complaint in 1748, for he − a “poor man with a large family” − had not received his salary since his appointment ten years prior. From 1676 onwards, the inhabitants of Carbonero el Mayor opened a quarry in the right bank of the Eresma river, and appointed themselves administrators there as well, in order to regulate the exploitation.

The subtle glow or radiance produced by the roofs was one of the determining factors in the final choice of the material and is mentioned in the orders given to the master of the works. The planning of the tasks is detailed in the same letter:

And so I ordered that eight apt skilled workers should be sought, two to extract the slate, four to cut, polish, and lay the pieces, and the last two to build the wooden frames for the roofs and assemble them. And they will shall depart in time to return back home for the spring. In the meantime, you must have the adequate wood chopped and smoothed down so that it is prepared for the roofs, and have men diligently search for slate as near the house as possible, so that the workers do not waste any time upon arrival…

The King even advises on the nearest location in which he has seen the material:

The nearest location in which [slate] can be found is in Santa María de Nieva. I was passing through there one day and I observed that slate was being used to build a church.

The reference to Santa María de Nieva is not coincidental, as the town was located on the route used by the Court when they travelled from Valladolid and Segovia. The origins of Santa María de Nieva − which was founded by the monarchy − are related to the discovery of the Virgin of Soterraña, and to the foundation of a monastery by Catherine of Lancaster, the wife of King Henry III, at the end of the 14th century. The town church is that which Philip II mentions in his letter.

The Flemish slate masters arrive to Valladolid in July of the same year, and two carpenters, Juan de Bruselas y Gutierre de Spina, were sent out later from Flanders by Cardinal Granvela. By 1562 the number of slate masters from Flanders had increased to eight: Regnesson de Wart, Jaequenin Hallart, Lienatt Tehoncur, Jean de la Ret and Nicolas Bonsar, all of them from Liege, as well as Jean Bonsart and Hans Bethemans from Antwerp and Gilles Marcq, from Lier. Each of them probably earned approximately 200 maravedis per day, regardless of whether it was a holiday or not. They were assisted by a naimaker named Juan Colin. More slate masters such as Juan Ru arrived from France at a later point, and the art of the trade started being taught to local masters such as Gonzalo López, one of the first Spanish slate masters. Another man to learn the trade was Pedro Muñoz, who arranged the slate for numerous works such as the Casa de la Moneda in Segovia, works around La Fuenfría, the towers of the Segovia town hall or the Palace of Lerma, and who ran the quarries of Bernardos as administrator for more than thirty years. Pedro Muñoz insisted that the work of a slate master ended at the moment of laying the slate on the roofs, as he made clear in a letter which he sent to the supervisor of royal works in 1623 reporting on the works in La Fuenfría:

Your Grace, I must warn you that the man who extracts the slate is not a slate master but an extractor, which is a distinct and different type of work.’’

M. Fougeroux, 1761, planche IV

(9) Archivo Histórico Provincial de Segovia (AHPS). Prot 8101, f. 832.

(10) La información de la época distingue entre sacadores borgoñones y franceses. En aquella época el ducado de Borgoña, que pertenecía a la Casa de Austria, era una entidad política distinta del reino de Francia.

(11) Archivo de la Biblioteca del Escorial (ABE) IX-17.

(12) ABE, VII-44, octubre de 1581.

(13) Fourgeroux, 1761, planche I, fragmento.

(14) Zarco Cuevas, p. 99 y ABE, instrucciones 1587.

(15) A BE-VII 44, Instrucción 1581

(16) Archivo General de Palacio (AGP), Reales Cédulas, t. XIII, fs 12v-13.

(17) AGP, Exp. Pers. 988/7.

(18) AGP, exp. Pers 222/37.

(19) AGP, Exp. Pers 988/15.