Company > History >Historical value of the Bernardos slates > Locating and selecting the deposits

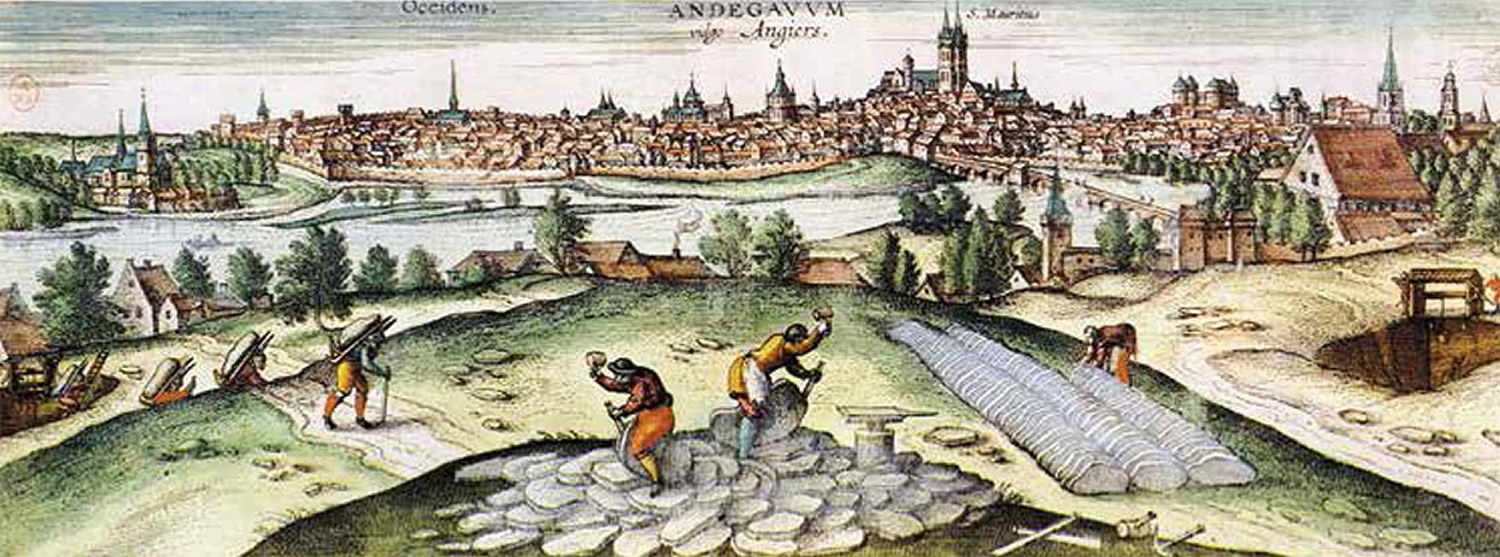

The foreign technicians who arrived to Bernardos around 1560 had to undertake a preliminary inspection of the area in order to select the most appropriate places to extract the ideal material for the works. They searched for areas which combined two main criteria: the quality of the material and the ease of extraction. They soon opted for the area in which the course of the Eresma river follows the valley formed by the fractures caused by tectonic movements in the slate-abundant mountain range. These fractures helped the formation of secondary streams, which drain the main river and lead to erosion throughout its course, thus leaving of the slate practically in bare sight. In sum, the slopes of this valley favours the opening of quarries.

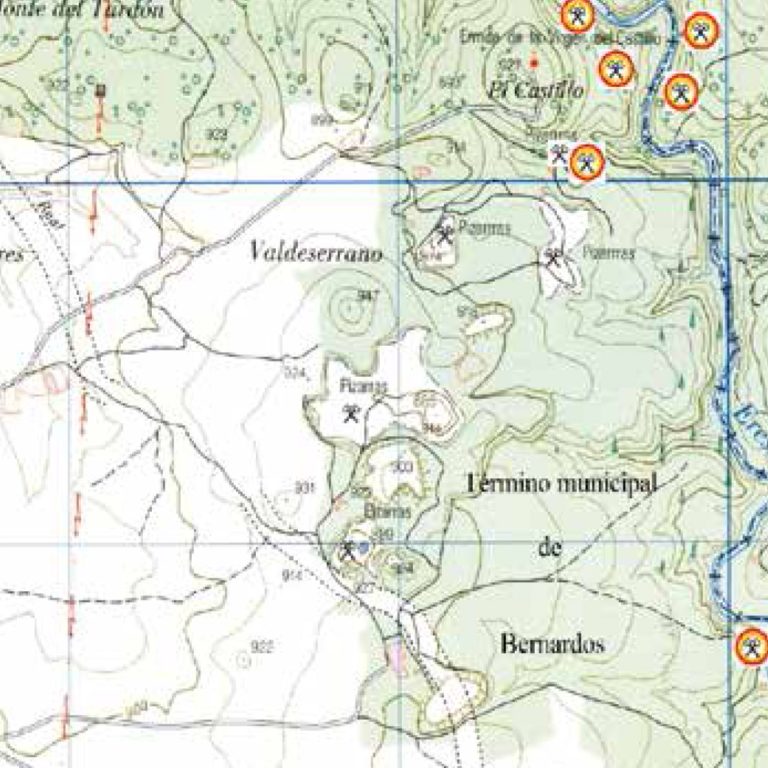

The eastern side of the Castillo hill, on the left bank of the river, was one of the first locations to be considered adequate. As can be seen on the map, the side has a steep slope which allows extraction from the banks without the need to clear too much debris, use wells or dig in great depth to extract the material. The only requirement was to clear the superficial part of the mountainside, remove the softer material and access the more compact layers. At the same time, while holes were dug, it was necessary to carry out draining operations to avoid any form of flooding. It appears that the extraction started in the lower areas, and progressively took over wider areas as more strata were uncovered. Thus, they could extract the material from below, digging sufficiently to benefit from the ease of access, widen the surface of the quarry while looking for better seams. Thereafter, once the strata of material from the lower area was extracted, the leftover debris made it easy to access the upper strata of the mountainside. Later on, further strata were discovered in nearby areas, such as the fountain of San Pedro and other locations closer to the river, which seemingly contained good material.

From 1563 with the arrival of additional technicians from France, other quarries were opened in the vicinity. Records show that a quarry was opened upstream from the Arco windmill, and slate was extracted there for years as activity in this area increased. In 1567, the administration of the quarry started receiving complaints about the problems faced by the windmill due to the debris which resulted from the extraction work and accumulated in the dam.

The exploitation of the deposits of the Eresma valley continued on throughout the 17th century and reached Carbonero el Mayor, which lies on the right side of the riverbank. The 17th century saw various quarries open on both sides of the river. The exact locations are difficult to identify due to the lack of documentation, except in cases such as the opening of the Valdeguerrera quarry during the midcentury. However, it must be noted that Bernardos still hosted the largest portion of the extraction work.

Those locations were given the name of Royal Quarries, and were usually situated in areas in which agricultural exploitation was impossible, that is, in empty lands without clear ownership and thus in the hands of the Crown. Therefore, the quarries were exclusively utilised for royal works, or for works which had received an authorisation from the Crown’s Committee on Constructions and Forests to be supplied with slate. The quarry administrator was in charge of supervising the extraction permits and of responding to the demand for the material which was processed through the Committee, until the needs of the construction of the Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial placed the administration of the quarries in the hands of monks from a Hieronymite congregation.

The quarry administrators sometimes reported breaches in the use of permits, as some extractors circumvented them to extended their scope to other works. The prohibition to divert slate without an administrator’s authorisation was thus often reiterated, with the warning that a high fine would be charged for such a breach. There were cases in which the transportation was stopped because the carriers did not have the adequate permit to transport slate, as was experienced by the neighbours of Carbonero el Mayor in the sale of Otero de Herreros in 1676.

(7) AGS Casa y Sitios Reales, 267: 1, fol. 201.

(8) Citado en Ceballos, 2010, p. 62.