Company > History >Historical value of the Bernardos slates > Origins of the quarries exploitation

Philip II arrived upon the throne of Spain at the beginning of 1556, following the abdication of his father − the Emperor Charles V. He thus became the most powerful monarch of his time, owning such a vast expanse of land that it was said that “the sun never set” over his territory. His reign lasted until his death in 1598. He was educated by excellent masters in a refined atmosphere, thanks to which he developed a taste for fine arts. It is worth observing that great masters such as Tiziano and El Greco worked as court painters for him. Art and architecture historians agree that slate was introduced in royal artwork during the reign of Philip II as a result of an exclusively individual decision by the monarch. This choice was based on his knowledge and taste in architecture which he acquired and developed as a prince throughout his trips accross in Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and England, to which he travelled to wed Queen Mary Tudor, his second marriage. In practice, however, slate was introduced by the architects who were working under the monarch’s orders: Juan Bautista de Toledo, Luis de Vega, Gaspar de Vega, Francisco de Mora, Juan de Herrera, etc. These men turned the monarch’s wishes into a reality.

The choice of slate was a response to the fascination which overtook the King when he observed the constructions built with that material during his trips accross in the countries mentioned above. His reign is a period of effervescent construction of royal buildings, located mainly between Segovia, Madrid and Toledo and coincides with the Court’s decision in 1561 to settle in Madrid as the Kingdom’s permanent capital city. The configuration of the new style implied a challenge as well as a commitment from the royal architects to reflect their monarch’s wishes in the buildings which they designed. One of the strongest characters involved in this regard came from Gaspar de Vega, who oversaw the construction of the Valsaín Palace and who also often visited other European countries, sometimes accompanied by Philip II himself. Gaspar de Vega took notes on the buildings which he saw during his visits, finding suggestions for his own drawings and designs.

The new architectural style entailed not only the adoption of a new material but also new techniques and the employment of new professionals to carry out some of the works, such as carpenters for the new roof structures. It was thus necessary to bring in new knowledge and people, as well as specific tools (such as nails to support the solidification of the slate, which were brought from Flanders) to help and disseminate the know-how among the local professionals.

1559 marks the start of the new construction process which incorporated slate in the construction of royal buildings. In the letters which Philip II exchanged with Gaspar de Vega, they pondered alternative options on materials to be used, and it was then that they decided to set aside lead. Although he was a proponent of this material, Gaspar de Vega mentions the issue of lead stains in a letter written to the King in January 1559. In his response, the King finds even more disadvantages in the use of lead(1) :

“The first problem is that lead would load up the house, and the other is that it would make it very warm in the summertime, as we have learnt from experience in this area. It appears to me that it would be best to build roofs in the manner of those states and cover them with slate, which, as you have seen, look magnificent…(2)“

The subtle glow or radiance produced by the roofs was one of the determining factors in the final choice of the material and is mentioned in the orders given to the master of the works. The planning of the tasks is detailed in the same letter:

“And so I ordered that eight apt skilled workers should be sought, two to extract the slate, four to cut, polish, and lay the pieces, and the last two to build the wooden frames for the roofs and assemble them. And they will shall depart in time to return back home for the spring. In the meantime, you must have the adequate wood chopped and smoothed down so that it is prepared for the roofs, and have men diligently search for slate as near the house as possible, so that the workers do not waste any time upon arrival…”

The King even advises on the nearest location in which he has seen the material:

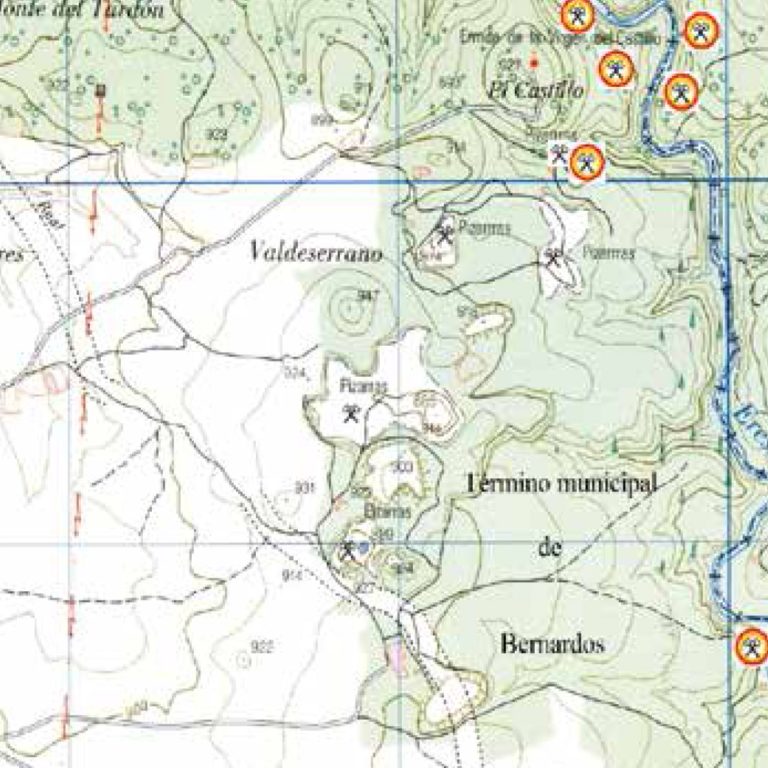

“The nearest location in which [slate] can be found is in Santa María de Nieva. I was passing through there one day and I observed that slate was being used to build a church.”

The reference to Santa María de Nieva is not coincidental, as the town was located on the route used by the Court when they travelled from Valladolid and Segovia. The origins of Santa María de Nieva − which was founded by the monarchy − are related to the discovery of the Virgin of Soterraña, and to the foundation of a monastery by Catherine of Lancaster, the wife of King Henry III, at the end of the 14th century. The town church is that which Philip II mentions in his letter.

The Flemish slate masters arrive to Valladolid in July of the same year, and two carpenters, Juan de Bruselas y Gutierre de Spina, were sent out later from Flanders by Cardinal Granvela. By 1562 the number of slate masters from Flanders had increased to eight: Regnesson de Wart, Jaequenin Hallart, Lienatt Tehoncur, Jean de la Ret and Nicolas Bonsar, all of them from Liege, as well as Jean Bonsart and Hans Bethemans from Antwerp and Gilles Marcq, from Lier. Each of them probably earned approximately 200 maravedis per day, regardless of whether it was a holiday or not. They were assisted by a naimaker named Juan Colin(3). More slate masters such as Juan Ru arrived from France at a later point, and the art of the trade started being taught to local masters such as Gonzalo López, one of the first Spanish slate masters. Another man to learn the trade was Pedro Muñoz, who arranged the slate for numerous works such as the Casa de la Moneda in Segovia, works around La Fuenfría, the towers of the Segovia town hall or the Palace of Lerma, and who ran the quarries of Bernardos as administrator for more than thirty years. Pedro Muñoz insisted that the work of a slate master ended at the moment of laying the slate on the roofs, as he made clear in a letter which he sent to the supervisor of royal works in 1623 reporting on the works in La Fuenfría:

“Your Grace, I must warn you that the man who extracts the slate is not a slate master but an extractor, which is a distinct and different type of work.(4)“

1) AGS, CC y SS. Reales, leg. 267: f. 61 “pero vinieron maltratadas, muchas de ellas horadadas (…) sería bien traerlo en balones y traer un oficial de los que lo hacen allá para que acá lo fundiese (…) y yo certifico a Vmag, que si no fuese por la mucha costa, que en toda esta casa del bosque sería gran bien hacerle todos los tejados de plomo”. El plomo fue un material utilizado en estos años en lugares como el Alcázar de Segovia y el palacio de Aranjuez.

(2) E. Llaguno “1977”, tomo II, pp. 198-9. En la carta, el Rey hace referencia al conocimiento de Gaspar de Vega de la arquitectura y el tipo de tejados del norte tras haber viajado y conocido zonas de Francia y los Países Bajos. Al respecto, L. Cervera Vera (1979). Sobre la atracción que despertaban los tejados de pizarra tenemos el testimonio por ejemplo de otro gran observador, M. de Montaigne “1994”, p. 29 que en el siglo XVI alaba las casas privadas en la ruta desde Suiza a Alemania¨ ”sans comparaison plus belles qu’en France, et n’ont faute que d’ardoises…” (Sin comparación, más bellas que en Francia, y solo las falta las pizarras…”).

(3)Cano de Gardoqui, 1991, p. 294.

(4)AGP, San Ildefonso, Cª 13536, 19, septiembre de 1623